- AROUND THE SAILING WORLD

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Email Newsletters

- America’s Cup

- St. Petersburg

- Caribbean Championship

- Boating Safety

- Ultimate Boating Giveaway

Class 40 Mighty Mites

- By James Boyd

- May 23, 2023

For sailing fans visiting from outside France, the Route du Rhum is a cultural shock, barely to be believed even once seen. It is France’s oldest singlehanded race, first held in 1978, and run every four years from St. Malo in northern France 3,500 miles across the North Atlantic to Guadeloupe. The fleet of 138 boats that assembled for the start in November 2022 was incredible, with an estimated value of 260 million euros—from the implausible 100-foot Ultime trimarans to a record fleet of 38 IMOCA 60s and a similarly impressive fleet of 55 Class40s. Dock sides are crammed with spectators, many hoping to catch a glimpse of the top skippers—some are genuine sports stars. Had the 2022 start not been delayed, French President Emmanuel Macron was to have attended. It’s that much of a big deal.

In the days and hours before the Route du Rhum started, more than 1 million people passed through its race village in St. Malo. In this environment, even non-French amateurs, such as the two US Class40 skippers, Alex Mehran and Greg Leonard, gained celebrity status with relentless autograph signing, selfies with fans and press interviews. Usually outshone by the bigger, higher-profile boats, the Class40 is the most successful 40-footer of all time. While the Farr 40 never topped more than 40 boats at a world championship, this is the second Route du Rhum in which more than 50 participated. To date, 192 Class40 hull numbers have been allocated.

While “Open 40s” once competed in the OSTAR and Around Alone, the Class40 came about independently. Born in France in the early 2000s, two designs defined the class: the Pogo 40 and the Jumbo 40. But the success and longevity of the Class40 is due to its highly constrictive box rule, drafted by a group that includes wise French sailor and journalist Patrice Carpentier, which remains robust 18 years on.

The box rule’s basic parameters are a maximum length overall of 39 feet, 11 inches; max beam of 14 feet, 9 inches; draft of 9 feet, 10 inches; average freeboard of 3 feet, 6 inches; max mast height of 62 feet, 4 inches; max working sail area of 1,238 square feet; minimum displacement at 10,097 pounds; and max water ballast of 1,653 pounds per side. Most brutal are the materials limitations: Carbon fiber, aramid, honeycomb cores and pre-preg resin are forbidden from the construction of the hull, deck, interior structure and fittings; go down below on one and, joyously, thanks to the GRP construction, it is not coffin black.

Carbon fiber is permitted for the mast, boom and bowsprit, while standing rigging must be steel rod. Sails are limited to eight, and all but two and the heavy-weather jib must be polyester and nylon. A single fixed keel and as many as two rudders are permitted, but daggerboards and foils are banned, as are canting, rotating masts, mast jacks, and adjustable or removable forestays. However, complex kick-up rudders are permitted. (Although their effectiveness to kick up in a collision is allegedly dubious.) Over the years, displacement and average freeboard have slightly reduced, but the biggest rule amendment has limited “how scow” Class40 hull shapes can be. While the latest foiling Protos in the Classe Mini (the “flying bathtubs”) are fully flat-bowed, Class40 has two max beam limits just short of the bow to prevent this. Naturally, costs have risen, but the rule has successfully limited them; today, a top Class40 costs 700,000 to 800,000 euros.

Those sailing the Class40s in the early days were a mix of pros and amateurs. Today professionals on sponsored boats are the majority. As for aspirant French pro sailors, the Class40 has become a significant stepping stone between from the Classe Mini and Figaro circuits to the IMOCA.

As skipper of Groupe SNEF , leading Mini and Figaro skipper Xavier Macaire says: “The transatlantic races like this [Route du Rhum] are very interesting to us, and the boat is not very expensive. The Class40 is easy to maintain and prepare, and is not a complicated boat like an IMOCA where you need 12 guys. With this, you need two or three, not full time. It is an easy, fast boat.”

With more top pros like Macaire joining, 30 new Class40s have been launched in the last four-year cycle. The most recent Route du Rhum podium, for example, comprised two-time Solitaire du Figaro winner Yoann Richomme ( Paprec Arkea ) and Mini Transat winners Corentin Douguet ( Queguiner-Innoveo ) and Ambrogio Beccaria ( Allagrande Pirelli ) of Italy.

Of the French classes, the Class40 and the Mini remain the most cosmopolitan, with entries from other European countries, notably Italy at present, while the United States, Australia and South Africa were also represented in the Route du Rhum. Far from being put off by the pro element, Americans Alex Mehran and Greg Leonard were thrilled to be on the same starting line. “It is such a privilege to race against some of the top offshore sailors in the world,” says Leonard, who hails from Florida. “It is like playing football against a first team in the NFL—it is that level of quality. There are not that many sports you can do that in.”

Both American skippers came to the Route du Rhum from similar paths. With his Mach 40.3 Kite , Leonard is a professional economist originally from Texas. He campaigned a J/120 for many years with his remarkable son Hannes, who raced his first doublehanded overnighter with his father at age 13. Now 18 and with thousands of race miles under his belt, both in the US and Europe, he is a Class40 expert. For his father, the Route du Rhum was his first singlehanded race.

Over the years, several top shorthanded sailors, notably British Vendée Globe skippers Mike Golding and Miranda Merron, have raced with him, also coaching him. He is very enthusiastic about the Class40: “They are beautiful boats, such fun to sail. When we delivered her to St. Malo, we had 28 to 40 knots just aft of the beam, and we just hung in the low 20s boatspeed, and it was finger-light steering.”

Mehran skippers Polka Dot , which has the perfect pedigree, being Yoann Richomme’s 2018 Route du Rhum winner—a Lift V1 design. Growing up as part of the St. Francis YC Laser squad and subsequently a Brown collegiate sailor, he met Welsh Class40 designer Merfyn Owen in 2009 and raced one of his designs. Remarkably, he won his first major singlehanded race, the 2009 Bermuda 1-2. He subsequently graduated to an Owen Clarke-designed Open 50, in which he set a record in 2012’s singlehanded Transpac. He then went off, had four kids, and developed his commercial real estate business before getting the itch once more last year. He competed doublehanded with Owen in the 2021 Transat Jacques Vabre on an old Class40, but as Mehran puts it, “We needed to get something scow.”

He too has been receiving coaching from Merron and Golding, among others. According to Mehran, one of the most difficult things to explain to those back home is less the offshore-racing fever that afflicts French fans, but that their skippers are not multimillionaires. Instead, they come from a wide age group and all have commercial backing to either buy a secondhand boat or—if they are higher-profile, more accomplished or just plain lucky—build a new one. So, returning to the Route du Rhum podium, Paprec’s business is waste disposal (admittedly, its owner races his own Wally 107), Arkea is banking and insurance, Queguiner is building materials, Innoveo is an app-development platform, and Pirelli makes tires (its CEO has a Wally 145).

Over the last two decades, the Class40s themselves have evolved, despite Draconian design limitations. What started as cruiser-racers with fitted-out interiors became racer-cruisers and are now refined pure racers. They may not be black inside, but the build quality of the latest-generation designs is of the highest standard, and it seems no longer possible to buy a cruiser-racer.

A delight of the Class40 is that no one designer is dominant; eight different designs make up the 30 boats built over the last four years. Pogo Structures, last of the original builders, is on its fourth version of its Pogo 40, the S4, designed by Emirates Team New Zealand’s naval architect, Guillaume Verdier (who also designed Structures’ scow-bowed flying Proto Mini).

The man who developed the first blunt-fronted scow Mini, David Raison, produced the Max40, built by JPS in La Trinité-sur-Mer. Also built by JPS are Sam Manuard designs—the Mach 40.4, such as the 2021 Transat Jacques Vabre winner Redman , skippered by Antoine Carpentier (nephew of the original rule’s writer), and now its evolution, the Mach 40.5, of which two competed in the Route du Rhum.

In 2020, VPLP made its first foray into the class with the Clak 40, built by Multiplast, of which four raced in the Route du Rhum, the top finisher being Martin le Pape’s Fondation Stargardt. Etienne Bertrand, another successful Mini designer, had two Cape Racing Scow 40s in the race, while Allagrande Pirelli , believed to be the most expensive of the latest crop and campaigned by last year’s Mini Transat winner, Ambrogio Beccaria, is an all-Italian affair designed by Gianluca Guelfi and built by Sangiorgio Marine Shipyard in Genoa.

However, after the recent Route du Rhum, nosing in front in the design race is Marc Lombard with his Lift V2s, of which seven were racing, including Yoann Richomme’s winner, Paprec Arkea . Lombard is one of the longest continuous players in the Class40, and has worked with Tunisian manufacturer Akilaria on its RC1, RC2 and RC3 models since 2006, of which 38 were built. His latest designs have been the Lift, introduced in 2016; Veedol-AIC , one example, took Richomme to his first Route du Rhum victory. The Lifts were custom-built with a hull and deck made by Gepeto in Lorient, but finished off by the V1D2 yard in Caen, and were more precisely engineered and built than the Akilarias. They were superseded this cycle by the Lift V2, the most popular of the new Class40s, with seven competing.

For Richomme, the Route du Rhum was a small distraction from having a new IMOCA built. He entered the Route du Rhum to defend his title and stay race-fit. If the first Lift was an early scow, the present one is at the limit, to the extent that it has a bump in the hull 2 meters aft from the bow at the limit of where the Class40 rule restricts the max beam to prevent such extreme scowness.

The scow bow provides more righting moment, but it also does interesting things to the boat’s hydrodynamics. “With a pointy bow, the keel is more angled and creates more drag,” explains Richomme, who is also a trained naval architect. “When a scow heels, the hull is almost parallel to the keel, so sometimes when we go over the waves, we can feel the keel shudder when it is producing lift. The chine is low and therefore very powerful, and when we heel, it makes for a very long waterline length. Also, we have very little rocker, whereas other [new] boats have a lot, which creates a lot of drag so they don’t accelerate so well when they heel.”

The Lift V2 “is a weapon reaching,” Richomme says. “We can hold the gennaker higher than we used to. Last time, I didn’t even take one. But with the power going up, so have the loads, and we are having problems with the hardware. I have broken two winches already.”

A downside of the big bow and straight chine is downwind, where the technique seems to be preventing the bow from immersing. Paprec Arkea is typically trimmed far aft, including the stack and the positioning of the 1,653 pounds of water ballast (most new boats have three tanks each side), while its engine is 19 inches farther aft, and the mast and keel 11 inches farther aft than they were on his previous boat. They are 77 pounds below the minimum weight, which Richomme admits may be too extreme—during training they broke a bulkhead.

Otherwise, their increased cockpit protection is most noticeable on all the new designs (although not to IMOCA degrees), while most have a central pit area with halyards fed aft from the mast down a tunnel running through the cabin. On Paprec Arkea , a pit winch is mounted just off the cockpit sole. With the main sheet and traveler lead there as well, Richomme can trim from inside the cabin.

Most extraordinary about the scows is how fast they are. Anglo-Frenchman Luke Berry, skipper of Lamotte-Module Création , graduated from a Manuard Mach 40.3 to a 40.5 this year and says: “It is a massive improvement both in speed and comfort. Reaching and downwind, we are 2 knots faster, which is extraordinary.”

The top speeds he has seen are 27 to 28 knots. “Most incredible are the average speeds—higher than 20.”

This effectively turns yacht-design theory on its head, with waterline length and hull speed having less effect upon defining the speed of a boat that spends so much time planing. On the Mach 40.5, the waterline is just 32 feet, with a length overall of 39 feet. Compared to the Lift V2, it has more rocker, supposedly making it better able to deal with waves.

Nowhere is the speed of the latest Class40s more apparent than where they finished in the Route du Rhum in comparison to the IMOCA fleet. Paprec Arkea arrived in Guadeloupe ahead of 13 IMOCAs, or one-third of the way up the IMOCA fleet. Richomme says he used to sail on a Lombard-designed IMOCA 20 years ago, when they would make 10.5 knots upwind. “On a reach, I reckon we are faster than them now. We can do 20 to 22 knots average speed.”

Ugly seems to be quick, but when it comes to the Class40, beauty is in the eye of the beholder of the trophy.

- More: Class 40 , Offshore Racing , Print March 2023 , Racing , Sailboat Racing

- More Racing

Women’s America’s Cup Steps Over The Threshold

Life On The Edge As Vendée Leaders Dive South

SailGP’s Black Foils Start Season 5 With a Win

No Doubts in Dubai For Rebooted US SailGP Team

Firecrown Acquires Active Interest Media’s Marine Group

St. Petersburg Kicks Off Regatta Series With 5 Class Championships

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

THE CLASS40

What is a class40.

The Class40 is a monohull dedicated to offshore racing. This boat has existed since 2004 as an intermediate oceanic boat, between the Mini 650 (6.50m) and the 60-foot Imoca (18.24m).

A boat framed by a strict gauge: – Maximum length: 12.19 m. – Maximum width: 4.50 m. – Maximum draft: 3 m. – Maximum air draft: 19 m. – Maximum displacement (weight): 4,500 kg. – Maximum sail area: 115 m2. – Ballasts: 1,500 liters. – Fixed keel and mast (tilting keel and tilting mast prohibited). – Maximum removable bowsprit: 2 m. – Average freeboard: must be at least equal to 1.08 m. – Daggerboard and foils prohibited. – Several prohibited materials such as carbon and Kevlar.

Today more than 170 boats have left the sites with a panel of international architects and runners from all backgrounds of sailing, and even from other sport.

Class40 Globe40 the great race by labernik on Sketchfab

The Class40 in action

Credit: Jean Marie Liot

- Skip to navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

- PRESTO! FOR SALE

- Raceboats/Dinghys

- Sharpies – Presto Boats™

- Race / Cruise

- Fast Cruising

- Performance Upgrades

- Structural Engineering

- Architectural / Industrial

- News & Media

Class 40 “Icarus Racing” 40' / 12.19m

The first Class 40 to be designed and built in the United States. Currently being campaigned by Jeffrey MacFarlane. http://jefferymacfarlane.com/

Yacht Specifications

| 40' / 12.19m | |

| 14.75' / 4.5m | |

| 9.84' / 3m | |

| 10255# / 4650kg |

“ICARUS RACING” – the first U.S. built Class-40

Build of the boat is by Ted Brown and Stewart Wiley of Al Fresco Composites, Portsmouth, RI.

To begin the design process we decided to test a series of hulls in a weather matrix for the race as well as a long-race performance predicition tool developed in-house by RMD. Class 40 is a ‘box rule,’ so we investigated one shape overtly maximized to the box. The other extreme was considerably narrower than the maximum, with a single rudder, lighter hull and a higher ballast-ratio, both to the minimum displacement. A third boat tested was between these extremes. For these three exploratory types, we used a ‘parent/child’ annex to our Velocity Prediction Program (VPP). This allows the boat to choose the location and amount of ballast (including ballast to leeward or empty) to give the boat its best performance in every wind strength and direction. Of course it doesn’t take into account sea conditions, exhaustion, broken gear and the indefinable issue of seakindliness. If it did, we could leave it all to the machines!

An intuition that a subtle step further was needed, led to the final hull choice. It was faster in the weather matrix and RMD’s own RTW test by a greater margin than all the others. We were on our way and sent the surface files to Goetz Custom for computer cutting. Design partner, Ross Weene has worked wonders (and long hours) to complete this program efficiently and accurately.

Spars are by Halls Spars of Bristol, RI. Sails are North 3Di. Steve Koopman, Dirk Kramers’ partner in SDK Structures has worked with Ross to engineer advanced light, durable hull and appendage structures with materials from Rich O’Meara’s ROM Composites of Newport.

This is not only an all-out US entry into Class 40 and ocean racing arena, but an all-Rhode Island entry too.

ICARUS RACING SAILPLAN (pdf)

ICARUS RACING COMPOSITE PLAN (pdf)

- New Sailboats

- Sailboats 21-30ft

- Sailboats 31-35ft

- Sailboats 36-40ft

- Sailboats Over 40ft

- Sailboats Under 21feet

- used_sailboats

- Apps and Computer Programs

- Communications

- Fishfinders

- Handheld Electronics

- Plotters MFDS Rradar

- Wind, Speed & Depth Instruments

- Anchoring Mooring

- Running Rigging

- Sails Canvas

- Standing Rigging

- Diesel Engines

- Off Grid Energy

- Cleaning Waxing

- DIY Projects

- Repair, Tools & Materials

- Spare Parts

- Tools & Gadgets

- Cabin Comfort

- Ventilation

- Footwear Apparel

- Foul Weather Gear

- Mailport & PS Advisor

- Inside Practical Sailor Blog

- Activate My Web Access

- Reset Password

- Customer Service

- Free Newsletter

Catalina 42 Mk I and Mk II

Beneteau First 42s7 Used Boat Review

Pearson 303 Used Boat Review

Grampian 26 Used Boat Review

Special Report: How to Prevent AIS and VHF Antenna Malfunction

Vesper Marine WatchMate 850 and Icom M91D: Where Credit is Due

How to Create a Bullet-Proof VHF/SSB Backup

Tips From A First “Sail” on the ICW

Haul Out Tips to Avoid Confusion and Delays

Checking Rope Strength

Lashing for Strength

Are Wrinkles Killing Your Sail Shape?

Ensuring a Safe Space for Batteries

Impact of Modern, Triangular-Design on Boat Performance

Keel and Rudder Design Basics

Diesel-Electric Hybrids Vs. Electric: Sailing’s Auxiliary Power Future

Wooden Boat Revival: Can Boatbuilding Be Regenerative?

How to Make Dodger Cover Canvas Pattern

How Much Does It Cost to Keep a Boat on the…

Insurance For Older Sailboats

PS Advisor: Acid Cleaning Potable Water Systems

Product Hacks: Velcro, Bounce, Anti-Skid Mats and Pool Lights

Stopping Holding-tank Odors

Giving Bugs the Big Goodbye

Five Best Cheap Clothing Options for Cold-Weather Sailing

How to Scuba from Your Boat

Compact Scuba Kits for Sailors

Cold Weather Clothes to Extend the Sailing Season

Bilge Pump Installation and Maintenance Tips

Full-Time Ocean Trash Cleanup in the Arctic Circle

Boats That Fly? How High Tech Rocked the America’s Cup

R. Tucker Thompson Tall Ship Youth Voyage

On Watch: This 60-Year-Old Hinckley Pilot 35 is Also a Working…

- Sailboat Reviews

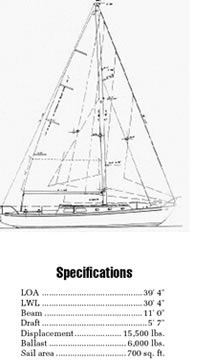

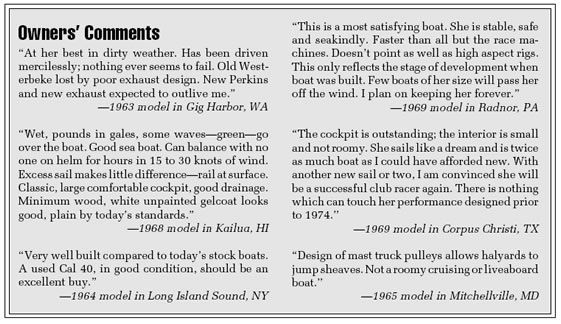

Though now an old and dated design, the Cal 40 was a hot boat when new, and she carries that legacy.

Thunderbird, a Cal 40 owned by IBM president T. Vincent Learson, took first in fleet over 167 boats in the 1966 Bermuda Race. Because this was the first computer-scored Bermuda Race, Learson got a lot of gaff about the IBM computer that had declared him the winner—and about beating out his boss. Thomas J. Watson, IBM’s chairman of the board, sailed his 58′ cutter, Palawan, second across the line, but ended with second in class, 24th in fleet, on corrected time.

In fact, the computer scoring system was not especially kind to Learson. Both he and Watson would have fared considerably better under the old system that calculated scores from the NAYRU time allowance tables. Thunderbird’s victory was a legitimate win, another in a stunning series by Cal 40s that was establishing the boat as a revolutionary design. The first Cal 40 was built for George Griffith in 1963. That winter, hull #2, Conquistador, took overall honors in the 1964 Southern Ocean Racing Circuit (SORC). The Transpac races of 1965, ’66, and ’67 all went to Cal 40s. Ted Turner’s Cal 40, Vamp X, took first place in the 1966 SORC. In the ’66 Bermuda Race, five of Thunderbird’s sisterships finished with her in the top 20 in fleet, taking five of the first 15, four of the first nine places. And so on. In their first few years on the water, Cal 40s chalked up an astonishing record.

The 40 was the fifth in a line of Cal designs that C. William Lapworth did for Jensen Marine of Costa Mesa, California. Lapworth had already designed a series of moderately successful racing boats, the L classes, including an L-24, L-36, L-40 and L-50, when he teamed up with Jack Jensen. The Cal designs were built on concepts he had tried in his Lclass boats. The first Cal was the 24, Jensen’s first boat, launched in 1959. The Lapworth-Jensen team then produced a 20, 30, and 28 before getting to the Cal 40, which proved to be a successful distillation of Lapworth’s thinking up to that time.

Aspects of the boat that departed from the conventional wisdom were her light displacement, long waterline, flat bilges to encourage surfing, fin keel and spade rudder. The masthead rig is stayed by shrouds secured to chainplates set inboard of the toerail, a then unusual innovation that allows a reduced sheeting angle. The success of the design helped legitimize fiberglass as a hull material, establish Jensen Marine as a significant builder of fiberglass boats, and propel Lapworth to the forefront of yacht design.

Three decades have passed since Lapworth drew the Cal 40. In that time, using computers to score races has become commonplace—boat measurers and designers would be paralyzed without them. The CCA Rule, the NAYRU tables and the Portsmouth Yardstick have been replaced by IMS, IOR, and PHRF, with the effects of their parameters expressed in the shape, size and weight of new boats. New building materials and techniques have changed the meaning of terms such as “light displacement,” “long waterline,” “fin keel,” and “fast sailboat.” Today the Cal 40 is a dated design, having been surpassed in her revolutionary features by her descendents. She remains among the esteemed elite of racing yachts, but she is not especially light, long on the waterline, or fast compared to current designs.

The Cal’s builder was transformed by time, as well. Jensen Marine was bought by Bangor Punta Marine, and the Cal production line was moved to Florida about the time that the Cal 40 went out of production in 1972. For the next decade, the company’s name and address shifted between combinations of Cal, Bangor Punta and Jensen in California, New Jersey and finally Massachusetts, where it joined O’Day under Bangor Punta’s umbrella in the early 1980s. After 1984 the company was called Lear Siegler Marine, Starcraft Sailboat Products, and finally emerged as Cal, a Division of the O’Day Corporation, in Fall River, Mass. Cal and O’Day ceased production in April, 1989.

Construction The construction of the Cal 40 is typical of Jensen Marine boats of the 1960s. The hull is solid hand laid fiberglass with wooden bulkheads and interior structures. Strips of fiberglass cloth and resin secure the wooden structures to the hull, but this tabbing is rather lightweight and has been reinforced in some Cal 40s where it has failed. If it has not been reinforced, it probably needs it.

Because saving weight was a priority in building the Cal 40, the reinforcement provided by the bulkheads and furniture is critical to hull stiffness. Failure of the bonding can be a significant structural concern.

The hull-to-deck joint is an inward-turning hull flange, upon which the deck molding is bonded, then through-bolted and capped with a throughbolted teak toerail. This is a strong type of joint, but there is some complaint of minor leaking along it in a few boats. The leaks are most likely one result of the relatively light construction of the hull skin, which has a tendency to “oilcan” in heavy weather, creating stresses at the joint.

The deck, also a solid fiberglass layup, has reinforcement designed into it during layup, so no interior metal backing plates are provided under winches, cleats, and other hardware. PS generally recommends backing plates behind high-stress hardware as a matter of course. We found little indication of trouble with leaking or working of most of the fittings, but one owner said that his lifeline stanchion bases had to be reinforced. This would be an area to inspect carefully.

Colors and non-skid surfaces are molded in, but due to the age of any Cal 40, the finish will look tired unless it has been renewed. A good Awlgrip job will do it wonders, and is probably warranted for this boat unless it is in general disrepair.

The deck and cockpit of the Cal 40 we inspected have numerous cracks in the gelcoat in corners and other stress areas. Check these areas closely—they are unsightly, but in most cases are not a structural concern.

Ballast is an internal lead casting dropped into the keel before the insides were assembled. If there is evidence that the boat has suffered a hard grounding, invesitgate the ballast cavity to see that it was properly repaired. It should not have a hollow sound when rapped, and there should be no cracks, weeping, or other evidence of moisture inside. Due to the construction sequence, major repairs could be awkward.

Wiring was also installed prior to the interior, which makes it quite inaccessible in some areas. What may be of more concern is that it is low enough in the boat to get wet if the last watch forgot to pump the bilges and the boat heels over to her work. That’s what happened to one owner, who lost all the electricity on the boat when approaching Nova Scotia’s Bras d’Or Lakes after an all night sail. Fortunately, dawn arrived in time to avert a navigation problem. They anchored in the harbor and found that the electrical system worked fine, once it got dry again. Before the next season rolled around, the boat’s entire electrical system had been replaced in elevated, accessible locations. The implication is that you should look carefully at the wiring in a Cal 40 before you make any decisions. If it has been replaced, try to learn who did the work and how well qualified he/she was for the job. If it has not, you may have to work the cost of rewiring into your acquisition expenses. We would suspect the worst until proven otherwise.

You might expect wheel steering on a boat this size, but the stock Cal 40 came with a big tiller. The boat is well enough balanced to be controlled with a tiller, and many helmsmen prefer it to a wheel, which masks feedback from the rudder and makes sensitive steering more difficult.

The cockpit is roomy, but properly designed for offshore work with relatively low volume, a bridgedeck and small companionway. The tiller sweeps the cockpit midsection, allowing the helmsman to sit fairly far forward, a help to visibility.

Winch islands are located aft of the helmsman, where there is room for the crew, but it also makes the sheets accessible to the helmsman for shorthanded sailing. The teak cockpit coaming has cutouts giving access to handy storage bins.

The aluminum mast is stepped through the deck to a fitting that meets it at the level of the cabin sole. The shroud chainplates are secured to a transverse bulkhead at the mast station, and then tied into an aluminum weldment in the bilges. This weldment also supports the mast step. While chainplates have been an area of concern in some designs, because they can work under the large loads they carry, our indications from Cal 40 owners are that the chainplate/shroud/mast step attachments have served well.

Sailing Performance The Cal 40 is in her element in heavy air, especially off the wind. Her long waterline and flat bilges help her get up and go on reaches and runs, surfing in heavy air. On the wind, the flat hull forward pounds in waves and chop, which slows the boat somewhat and is irritating. Owners agree that she sails best with the rail in the water. She is not dry on the wind, so a dodger is a welcome feature.

The masthead sailplan allows relatively easy reduction of headsails to suit heavier conditions, and Cal 40 owners extol the survivability of their boats. “Simple rig, nothing breaks, strong, easy to use,” is a typical comment. Despite her stellar racing record, the Cal 40 is only ordinary in performance by today’s standards. She carries a PHRF rating between 108 and 120 seconds per mile, depending on the region. That’s about the same as a C&C 38 or an Ericson 36, both IOR designs of the late 70s. Compared to a mid-1970s design such as the Swan 38, the Cal 40 is a bit slower on the wind and in light air, a bit faster off the wind and in heavier going, about equal in speed overall. It’s not surprising that these boats perform alike if you look at the length of their waterlines and their displacements.

In comparing the Cal 40 to boats of her own vintage one sees what all the fuss was about. The Columbia 40, for example, is a 1965 Charles Morgan design, an “all-out racer” with a 27′ waterline, displacement of 20,200 pounds, and a PHRF rating of about 170. Or look at the Hinckley 41: 29′ on the water, 18,500 pounds, PHRF about 160.

The Cal 40’s waterline is almost 31′, but she displaces one or two tons less than the Columbia or the Hinckley, and rates nearly one minute per mile faster under PHRF. In that context, she is indeed a fast, light displacement boat with a long waterline. Just look at her “fin keel” and you can see the progression. Compared to a full keel with attached rudder, it is small. Compared to a modern fin keel, it hardly seems small enough to qualify for the name. If Cal 40s win races today, it’s because they are well sailed, not because the boat is the fast machine on the race course.

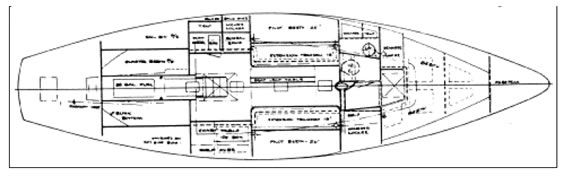

Interior In the 60s, “accommodations” tended to imply the number of berths in a sailboat, and the more the better. It also included the notion of a basic galley with sink, stove, icebox, and a table of sorts, plus a head with toilet and sink. Space age electronics had not arrived in the galley or the nav station, nor had space arrived in the concept of the main saloon.

Inside, as elsewhere, the Cal 40 is well designed and functional, but she speaks of her own era. The layout is very traditional, with a V-berth forward, separated from the main cabin by a head and hanging locker. Pilot berths and extension settees port and starboard provide sleeping for four. The dropleaf table seats four, six if you squeeze. Next aft is the galley to port and a nav station to starboard, consisting of a chart table over the voluminous icebox. The galley has a usable sink next to the well for a gimbaled stove with oven.

Flanking the companionway steps are the entrances to the quarterberths, known affectionately as “torpedo tubes,” which gives you an impression of their dimensions. They extend from the main cabin through to the lazarette, which allows good circulation of air. In fact, on a return trip from Bermuda, one seasick sailor found great solace between tricks at the helm by climbing into one of the cocoon-like torpedo tubes, where he was washed with a fresh breeze from the dorade vent on the lazarette cover. The fact that the quarterberths flank the engine compartment doesn’t matter as long as you are under sail, but it’s a different story when under power.

So you have sleeping accommodations for eight, which is too many people on a 40-footer, except perhaps when racing. The extension transom berths, however, do not lend themselves to use under way. The interior, not spacious by modern standards, fills up fast with extra bodies aboard. Owners tend to convert some of the berths to storage space. The pilot berths are especially tempting for that use, but since they are also the most comfortable berths on the boat, the quarterberths are often sacrificed for storage.

One of the best features about the Cal 40’s interior is the dining table. Set slightly to port, it is supported by a sturdy sole-to-overhead stainless steel post at each end with a 4′ 4″ gimbaled mahogany tray between them above the table. The posts make excellent handholds, and the gimbaled tray can serve for everything from salt and pepper holder to bookshelf to diaper-changing table. The table has a drop leaf to port and to starboard, so it can be set up for use from the port settee without blocking fore-and-aft passage through the boat.

Engine A variety of powerplants will be found in Cal 40s. Some early hulls were equipped with Atomic 4 gasoline engines. Later hulls got Graymarine 4-112 gasoline or Perkins 4-107 diesels. It’s likely that the original engine will need to be replaced if it has not already been done. Even the newest Cal 40s are rather old, and the early models have passed the quarter-century mark.

Boats in our files have Volvo MD2B, the Perkins, Pathfinder 50, Westerbeke 4-108, and Pisces 40 from Isuzu listed as replacements for the original engine.

The engine is located under the cockpit, between the torpedo tubes, which allow access to both sides, but are not especially convenient, particularly if the area has been turned into storage space. Better is the companionway ladder, which removes to expose the front of the engine. That can be an inconvenience, too, if the engine needs some attention while under way.

Used for the minimum requirements of a racing yacht, primarily getting in and out of port, you can probably make do with any of the engines. If the boat is to be used for cruising, with greater demands to be made on the engine, the Atomic 4 would likely be inadequate.

Generally the boat will do about six or seven knots under power, depending on the power plant and propeller. We suspect that many Cal 40s will have folding propellers, good for racing but not the best for powering, especially in reverse. The spade rudder set well aft confers good maneuverability under most conditons.

Conclusions The Cal 40, a hot racing boat when new, carries that legacy with her into maturity. Generally, the boats have been raced hard, some cruised hard as well.Owners have tended to be the type to add gear and modifications to keep the boat comfortable and competitive. The boats are likely to have a large inventory of much-used sails.

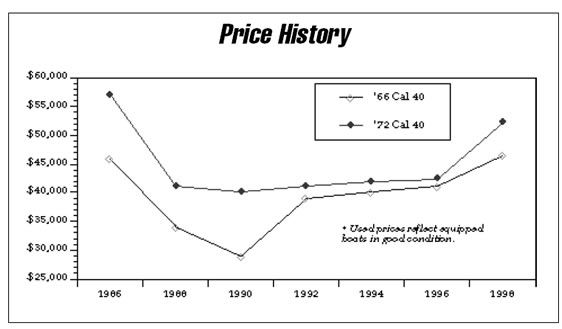

Because of her age and dated design, a Cal 40 may be available for much less money than a newer boat offering comparable quality and performance. Prices will vary according to the condition of the boat and gear, but will likely fall in the range of $40,000 to $50,000. If the boat has lots of add-ons in the galley and nav station, modern racing hardware, renewed standing rigging, new finish on the topsides, and the bottom is in good condition, it might fetch something higher. One performance extra to look for is a special (non-factory) fairing job on the keel and rudder that was available when the boats were young.

On the other hand, it should not be a surprise if there are areas that require attention, and you should calculate the cost of the work into the price you are willing to pay. Twenty or 25 years of hard sailing will take its toll. Significan’t expense could be incurred if the boat needs new wiring, an Awlgrip job on the topsides, extensive reinforcement of the interior furniture tabbing, a new engine, or new rigging. If racing is in your plans, new sails might be scheduled in as well.

This would be a good boat for a handy do-ityourselfer. Over the years, most of the boat’s problems have been solved more than once by other Cal 40 owners, many willing to share their wisdom. You would probably have a choice of solutions, and indications of which worked best.

Although there is not currently an active owners association, there persists a loose fellowship among present and former owners. If you buy a Cal 40, you will acquire a modest boat, with good pedigree and performance, and—should you desire them—a few new friends, as well.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Log in to leave a comment

Latest Videos

24 Knot Speed Trimaran – The Dragonfly 40 Ultimate

AMAZING Sailboat Drones, US Navy Deploys 65 Foot Sailing Drone

The SHOCKINGLY Comfortable Million Dollar Sailboat From Moody

New Sailor CRASHES and Needs Advice!

Latest sailboat review.

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- Online Account Activation

- Privacy Manager

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Now with more than 160 boats, the Class has become the most successful offshore racing class. The class is not to be confused with the Open 40 which in many ways led the way to this class. The "Class40" can be designed by anyone provided the boat fits within the measurement rule defined. This rule takes the form of a box rule.

The rig dimensions above are from the 1963 sail plan drawing. Current class rules (2005) allow a max of: I – 46.7′ J – 15.3′ P – 40.1′ E – 17.55′ The accolades for this particular boat are many. Certainly one of the most influential designs and successful racing boats ever. With 160 built, it […]

The Class40 is a monohull sailboat sea-oriented racing and cruising with a maximum length is 40 feet. The original goal of the class was to make offshore races accessible to amateur sailors. The success of the class has moved it beyond these parameters, with more and more professional sailors attracted to it.

A monohull is a boat with a single flotation plane at rest or under sail, whose hull depth in any transversal section shall not decrease towards the centreline. The current World Sailing (RRS, ERS and OSR) rules apply. The Rules for Class 40 Monohulls are the open type set out in Paragraph C.2.3 of the ERS (Equipment Rules of

May 23, 2023 · The box rule’s basic parameters are a maximum length overall of 39 feet, 11 inches; max beam of 14 feet, 9 inches; draft of 9 feet, 10 inches; average freeboard of 3 feet, 6 inches; max mast ...

The Class40 is a monohull dedicated to offshore racing. This boat has existed since 2004 as an intermediate oceanic boat, between the Mini 650 (6.50m) and the 60-foot Imoca (18.24m). A boat framed by a strict gauge: – Maximum length: 12.19 m. – Maximum width: 4.50 m. – Maximum draft: 3 m. – Maximum air draft: 19 m.

measurement expenses shall be paid by the person responsible for that boat). Any modification having a bearing on the Rules shall be brought to the attention of the Class Measurer and of the Class secretariat. A disabled sailor in Class40 may request that a specific dispensation be considered. The official language of the class is French.

Class 40 . www.class40.com. International Class 40 web site. Related Sailboats: Sort by: ... 5 Sailboats / Per Page: 25 / Page: 1. 0 CLICK to COMPARE ...

Class 40 is a ‘box rule,’ so we investigated one shape overtly maximized to the box. The other extreme was considerably narrower than the maximum, with a single rudder, lighter hull and a higher ballast-ratio, both to the minimum displacement. A third boat tested was between these extremes.

Jun 14, 2000 · In comparing the Cal 40 to boats of her own vintage one sees what all the fuss was about. The Columbia 40, for example, is a 1965 Charles Morgan design, an “all-out racer” with a 27′ waterline, displacement of 20,200 pounds, and a PHRF rating of about 170. Or look at the Hinckley 41: 29′ on the water, 18,500 pounds, PHRF about 160.